MUCH TALK ABOUT RESTAURANTS and eating these days, what with the new guides to San Francisco Bay Area restaurants from both Zagat and Michelin. We eat out a lot, though not so much in this area as when we’re traveling. We use both those guides, though of course we haven’t yet used Michelin’s San Francisco guide; it just appeared.

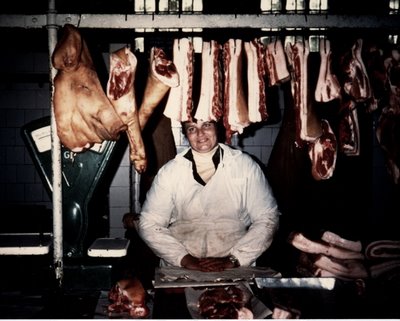

My attitude toward eating, I’m afraid, is signalled by the photo you see up there. It’s a misleading photo for it suggests plenty, both because of those hanging porcine pieces and because of the fetching butcher-lady herself, who clearly has not been starving. But the photo was not taken in a place of plenty: I took it on June 18, 1983, Saturday, in the market in Riga, Latvia. (I was there traveling with the ROVA Saxophone Quartet who were touring the then Soviet Union and Rumania.)

The market was given a large space, but there was little being sold. Quite a few enormous beets; a few tomatoes; some baskets of mushrooms, perhaps a few heads of lettuce. And, in a large covered area, a few stalls offering meat. This lady caught my eye as I went past: she was pretty and pleased to have a whole pig to sell, and when I lifted my camera and raised my eyebrows to ask if I might take her picture (for I know neither Russian nor Latvian, and knew it unlikely she knew English) she put her pretty hands together and tilted her head demurely and smiled.

I found the photo a couple of days ago while going through a few books. It was a 35 mm. slide originally, but I had two prints made a number of years ago, and misplaced this one. The other is at Chez Panisse, where I took it when a new butchering room was installed behind the kitchen, years ago. Like our Latvian lady’s stall, the room at Chez P. is tiled; but the carcasses hang in a walk-in cold room, and are brought out only when the actual butchering is being done.

(That last paragraph has just sent me to the dictionary. Butcher and slaughter, when I was a kid, meant two different things: you slaughtered a live animal (the word is cognate with “slay”); then you butchered the carcass, cutting it into manageable pieces. But though we were rustic enough to slaughter our own pigs, then butcher them out (for I think I recall the verb requiring its postposition), we were sophisticated enough even in those days to quibble over verbal precision: so maybe this distinction between slaughter/butcher was idiomatic to the Shere household.)

When you go through a period of butchering, not to mention slaughtering your own meat, you develop a pretty basic attitude toward eating. In fact you eat rather than dine. And that distinction is I think a significant one, and one addressed by those two guides, Zagat and Michelin. Zagat is a compendium of restaurant reviews — or, rather, a comparison of restaurants in terms of food, decor, service, and price — based on information sent in by large numbers of (usually) anonymous informants. The ratings run from 0 (or, more likely, 8 or so) to 30 in each of these categories.

The Michelin guide, on the other hand, is a list of restaurants grouped among only four levels of quality: three stars, two, one, or none. (True, there are qualifiers signalled by numbers of knives and forks, or the occasional red R rewarding a place offering unusual quality for the price. But these qualifers are far from the thrust of the ratings.)

Zagat is for eaters; Michelin is for devotees of fine dining. And, let me add, fine dining of a particular type: for Michelin takes the Zagat trinity of Food, Decor, and Service as a single item, and insists, I believe, on a certain kind of decor and service if it is to award anything beyond a single star.

Now I must point out that I’ve been associated with Chez Panisse since its opening, thirty-five years ago; and I do not pretend to any degree of objectivity when I write or talk about it — or, by extension, when I discuss any of the many establishments run by what you might call alumni of Chez Panisse.

On the other hand I do have decided opinions as to what constitutes not only Good Food (in the sense of Good Cooking), but also Good Eating — and even Good Dining. And as luck would have it just a day or two before the new Michelin appeared, scattering stars for the first time among Northern California restaurants, Lindsey and I ate for the first time at the one restaurant it rewarded with three of them: the French Laundry in Yountville.

I can well understand the Michelin rating, for the French Laundry reminded me of other three-star restaurants I’ve been to over the years — two in particular: the Auberge de l’Ill in Alsace and Girardet in Switzerland. Both those visits were years ago, of course; we no longer go to three-star restaurants — and that statement alone tells the story. We could go to them, I suppose; the only real reason we don’t is that we don’t enjoy them enough to pay the price.

We were taken to the French Laundry by a generous friend, and I hope he won’t find the rest of today’s blog ungrateful. We enjoyed the experience on several counts. We should know the place first-hand, of course; since we’re somewhat in the restaurant business we should experience every corner of it. Then too many of the dishes we had were quite delicious and all of them were technically absolutely first-rate (well, maybe one or two courses slipped just a bit).

And the wines we had — seven of them, to accompany the ten or so courses we managed — were really quite superb. Lindsey and I don’t drink this kind of wine; we can’t afford it. We discovered, though, that there are indeed California wines whose taste and finesse are at the top of their class: for example, Renard Roussanne from Santa Ynez, Selene Sauvignon blanc from the Carneros, and Martinelli Pinot Noir “Blue Slide Ridge” from a few miles out at the coast.

But — and you knew the “but” was coming — imposing and interesting and compelling as all this was, I didn’t leave thinking I’d had dinner. The French Laundry’s menu (you can see at example online) offers not a meal but a succession of events, each fascinating to see. (There are some splendid photos at the Bunrab blog — a fascinating blog to browse if you’re a foodie.) The events are wonderful and artistic, but to me it’s more like watching a gifted magician pulling rabbits out of hats than tucking into dishes prepared by a caring cook. It’s art, but art of a different order from the one I want at the table.

I wrote some time ago, in an introduction to my friend John Whiting’s Through Darkest Gaul, a friend’s guide to Paris bistros,

The art form of our time, the final thirty years of the twentieth century, has been the preparation of food. What the sonnet was to Elizabeth’s London, the Lied to Schubert’s Vienna, the easel painting to Impressionist Pontoise, the movie to the nineteen-thirties; that, to many of us, is the meal.

And I see that even this is out of date; it is no longer the meal but the individual course that is the art form. The hell with it, I say; let’s eat.

No comments:

Post a Comment